Overview

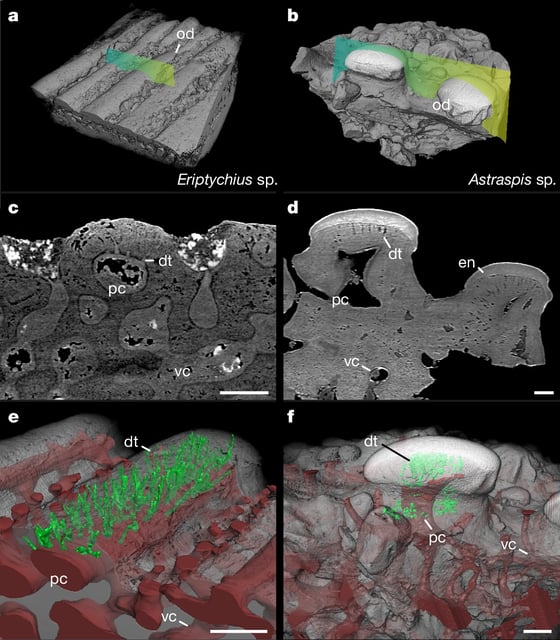

- New research identifies Ordovician fish like Eriptychius, dating to around 465 million years ago, as the earliest vertebrates with dentine-containing sensory structures called odontodes.

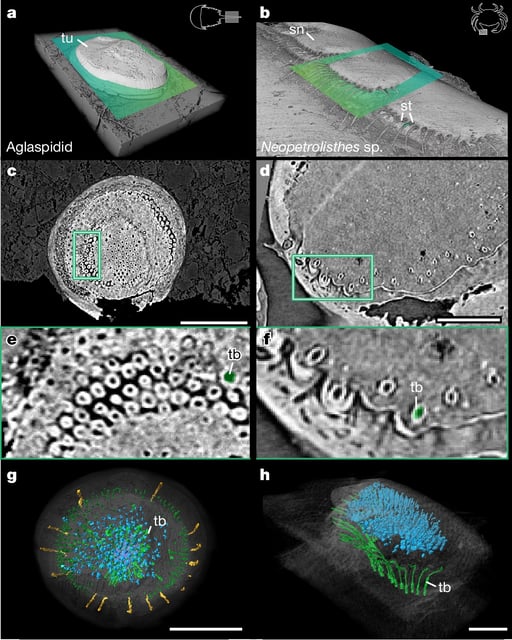

- Cambrian fossil Anatolepis, long thought to be an early vertebrate, is reclassified as an invertebrate arthropod with sensory organs similar to modern crabs' sensilla.

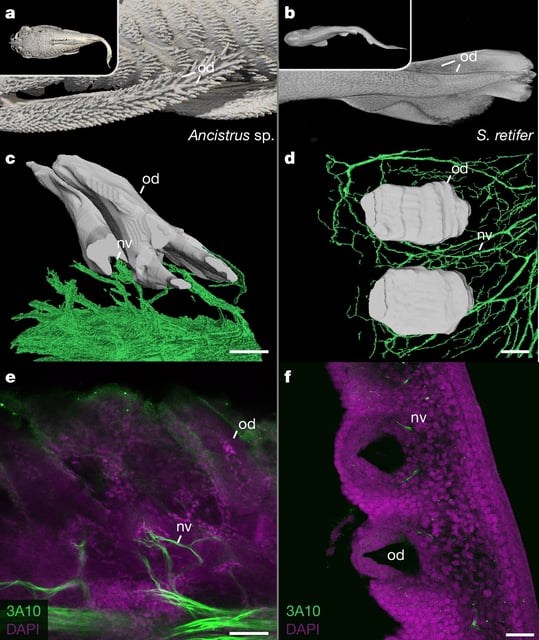

- Advanced CT imaging at Argonne National Laboratory visualized microscopic structures, confirming that early exoskeletal odontodes functioned as sensory organs before evolving into teeth.

- Modern fish such as sharks and catfish retain tooth-like skin denticles connected to nerves, demonstrating the sensory role of these structures across evolutionary time.

- The findings validate the outside-in hypothesis, showing that external sensory structures were co-opted into oral teeth through convergent evolution of sensory armor in vertebrates and invertebrates.