Overview

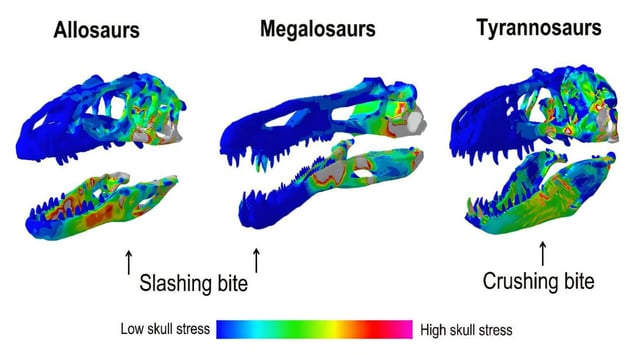

- Researchers applied CT and surface scans alongside finite element analysis to quantify skull mechanics and bite strength in 18 bipedal theropod species spanning 237–66 million years ago

- Tyrannosaurids such as Tyrannosaurus rex were found to have skulls optimized for high bite forces at the cost of elevated stress in the bones

- Spinosaurs, allosaurs and other large theropods exhibited weaker bite forces more suited for slashing and tearing flesh than for crushing bone

- Analysis showed no direct correlation between body size and skull stress, with some smaller species experiencing greater stress than larger counterparts

- Ongoing work aims to integrate these biomechanical insights into paleoecological models to refine our understanding of predator niche partitioning in Mesozoic ecosystems