Overview

- Researchers incubated wetted permafrost cores from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ tunnel near Fairbanks at about 3–12°C, observing minimal activity for months followed by sudden growth and visible biofilms.

- The experiments reveal nonlinear dynamics with a long lag before rapid population surges, indicating that the length of warm seasons matters more than isolated hot days for microbial activity.

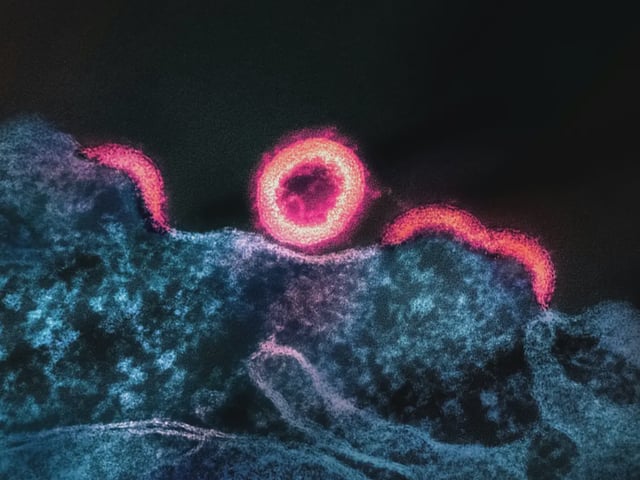

- The revived microorganisms can decompose ancient organic matter and release carbon dioxide, with potential methane emissions, raising concerns about climate‑warming feedbacks as permafrost thaws.

- The team reports biosafety controls and says the microbes they handled likely cannot infect people, while outside experts note unresolved risks that thawing permafrost could expose ancient pathogens or antibiotic‑resistant organisms.

- Findings come from a single Alaska site under controlled laboratory conditions, and related tracer studies documented community shifts over similar timescales, leaving behavior in other regions uncertain.